Defining the Entry Point

What do Sonos, Peloton, and AWS have in common?

Pete DeJoy | January 5th, 2021Meet your customers where they are, so you can take them to where you want them to go.

This truism rang through my head this holiday season as this year’s batch of next-gen gifts hit the shelves and blasted my Instagram and Twitter feeds. In an increasingly digital world, it feels as if the options for cool, physical toys to buy your loved ones dwindles every year. What used to be a gaming console and library of games on circular disks is now a giftcard to a cloud gaming server, what used to be an array of colorful plastic objects to keep the kids busy is now a few iPad apps.

Now that’s all good - I don’t think anyone will complain about having less clutter - but what’s going to happen with all of the hardware, all of the once-cool technology that has been bought & installed over the last 30 years? Consumers have still incurred the cost of purchasing stuff, and now they will need to take on the cost of disposing stuff if it no longer serves utility. That’s a tough thing to reconcile as a consumer; how do you justify all of the money you’ve spent through the years on plastic & metal relegated to a landfill if you wish to upgrade your rig to the latest & greatest? This is especially significant for cases in which the old hardware isn’t bad, but just isn’t as great as the new stuff.

Shiny New Toys

Sonos

I’ve been a big time Sonos admirer for many years; while a relatively young company (est. 2002), they’ve built an experience around listening that’s unparalleled by any major audio equipment manufacturer in my opinion.

But here’s the thing: high-fidelity audio has been around forever. Bose, Sennheiser, Sony, etc have been producing amazing high-quality speakers since the middle of the 20th century and, while some audiophiles may argue otherwise and cite frequency response patterns, high-fidelity audio is fairly commoditized.

It's not the hardware that makes Sonos special, it is the software.

Beautiful integration with streaming services, a wireless mesh network of speakers that can be selectively controlled, and smart features that allow the speakers to act intelligently per the shape and object profile of the surrounding room make the experience of using Sonos superior.

But still, categorically new software paired with commodotized hardware isn’t necessarily enough to create a significnat addressible market, especially when there exists competing legacy hardware that’s fairly ubiquitous; plenty of homes have existing wired stereo setups that are pretty damn good. To create a truly compelling product that can actually upend incumbents, Sonos would need to leverage their beautiful software experience as a gateway drug to their hardware. And in order to do that, they’d need to create a low entry point that would allow users to actually use the software without spending an arm and a leg on an entirely new Sonos speaker setup to fully replace their existing stereo system.

So they launched a category of products called Sonos System Products, which are designed to make third-party wired systems, stereo systems, and home theater set-ups look and feel like Sonos systems. With these products, currently titled the Port, Amp, and Boost, users can generate value from their old stereo systems, get the best of Sonos tech, and mesh together legacy hardware with new Sonos speakers to enable a cohesive modern experience.

Sonos differentiates with their software, then builds an easy upgrade path to bridge the gap between legacy and next-gen hardware.

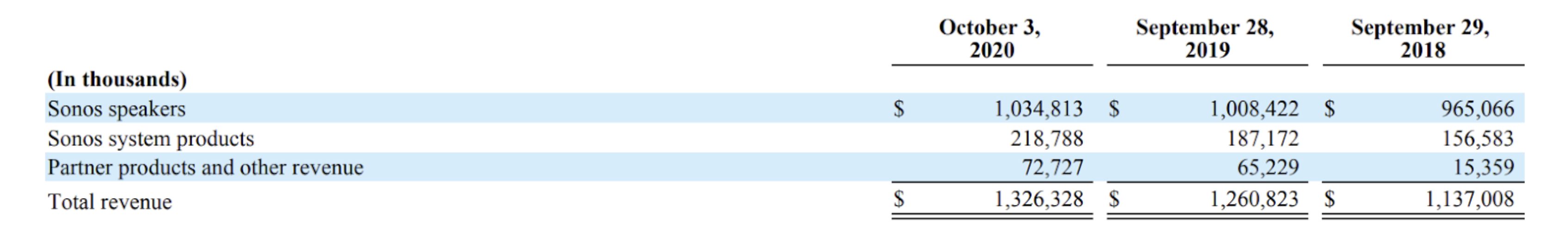

Interestingly, Sonos system products have accounted for almost all year-over-year growth since 2018 per their most recent 10-k. If I were to theorize, I’d suspect that once a certain scale is reached, driving categorical system growth will be followed by speaker growth as users are further engrained in the Sonos ecosystem and want to build on their existing network of hardware.

Peloton

I actually didn’t anticipate writing about Peloton at all in this post, but it popped into my head as a good anecdotal case study on using software to bridge the gap between legacy and modern hardware.

I’m a Peloton junkie. I started out as a Peloton app user, using it 3-4 times a week for about a year for treadmill, outdoor running, biking, or strength training workouts on reagular equipment at my gym. I became a pretty strong advocate of the brand and was a huge fan of the app experience and instructors that came along with it.

Then the pandemic hit and I could no longer go to the gym to hit the tread. In order to stay active, I’d need to invest in a home gym setup. It was an easy decision to pull trigger on the Peloton bike: I knew exactly what I was getting and had already proven to myself that their digital experience was well worth the money.

This story isn’t particularly interesting, but what is interesting is this: I know many people who went through this exact same buying journey. Get access to an account on the app, fall in love with it, buy a Peloton Bike or Tread to get the digital content delivered as a first-class citizen by high-end hardware.

Now, the Peloton case is a bit different from Sonos because most of their revenue comes from digital content subscription, while Sonos drives revenue from hardware sales. But Peloton hardware is more than just a distribution tool for their software. Sure, Peloton’s business is based on subscription revenue (which comes from their software), but subscriptions to their content costs about 3x as much if you own a bike than it does if you’re an application user-- $40/mo vs $13/mo or free if you know someone with a bike ;). Their bikes aren’t just a way to distribute software, but also are a way to upsell on the software subscriptions that users are already using and paying for.

To the Cloud

Taking a step away from consumerism, I can’t help but think this phenomenon has been modeled out for us by perhaps the most expensive enterprise technology trend of the 21st century.

Some Context

Traditionally, big companies have invested heavily in building out datacenters, which is just a fancy word for big buildings with lots of computers that the company’s employees can use to store files, deploy software, process data, run complex large-scale computation, and all of the other wonderful things that people can use computers to do. These datacenters are no joke; in order to build one out, you need to spend a ton of money. Property to actually store all of the hardware, a massive amount of servers, networking gear, security, and humans to maintain and monitor all of this physical infrastructure, and we’re just scratching the surface. Almost all major companies that have been around since the early 2000s have had to take on this expense, and all of them have felt the pain of maintaining these behemoths through the years.

Enter AWS

In 2002, Amazon launched Amazon Web Services with the goal of eliminating the need to incur massive up-front costs to leverage large-scale computer networks. Rather, Amazon would build out massive datacenters of their own and rent pieces of their servers to customers via a consumption-based pricing model. Now, rather than paying millions to build your own datacenter, a user would be able to just rent some real estate on Amazon’s at a major fraction of the cost.

Naturally, this made it quite easy to acquire greenfield customers; younger companies could now invest more heavily in R&D and Growth and forgo the traditional IT expenditure. But this wouldn’t be enough: how would AWS get the fortune 50s, the companies with big ol’ balance sheets and bottomless budgets on board? Marginally superior hardware would not be enough to convince the enterprise to abandon all of the legacy infrastructure they’d already spent millions building.

Software eats everything, etc etc

Amazon would have to differentiate with software to build an experience on top of their core infrastructure that made using their services in tandem with a homegrown datacenter more compelling. When you combine the superior tools & services with the lack of up-front cost, building your company on AWS infrastructure, or in the cloud, is a no-brainer; the availability of software for managing infrastructure & networks, data processing & storage, and building, deploying, & securing application could provide a differentiated path for AWS to engage with the traditional enterprise. This conceptually starts to build a bottoms-up narrative that’s much more palatable than a revolutionary one.

But stopping there would be inherently limiting. At the time, companies didn’t necessarily want a migration story, but rather a way to justify the cost they’d incurred in building out their IT muscles while having access to best-in-class technology that would make their engineers and IT professionals more performant.

The Hybrid Cloud is Born

And thus, a new era came into the picture in which companies would operate in hybrid contexts with some of their technology running on-premises (ie. in the servers in their datacenter) and some of it running in the Cloud. This would allow companies to drive value from all of that expensive hardware that they had already purchased while also using the highly-differentiated software built, supported, and maintained by the major cloud providers. This got especially interesting as Cloud providers got more mature and started launching services that catered to the hybrid model like AWS Outposts, which allows you to operate AWS software on top of your own hardware :shocked-face-exploding-head:. With tools like Outposts, companies no longer need to rent hardware from AWS to have access to their superior software. This concept breathes new life into the datacenter that has persisted through the years: companies no longer need to operationalize both their own hardware and a cloud environment, but rather can drive incremental value from core infrastructure so that is now more valuable than the sum of its parts.

AWS has been able to effectively use the leverage created by their superior software to operationalize and bridge the gap between legacy and modern hardware. \

The Bottoms-Up Playbook

There are plenty more examples of these strategies, but these three stood out to me as interesting case studies in how companies use differentiated software to drive hardware adoption. With that, there is an interesting overarching narrative here that applies universally to consumer and enterprise growth models implemented by Sonos, Peloton, and AWS. If you can manage to implement a model that:

- Builds a compelling and differentiated user experience with software.

- Make it easy to use your software in tandem with legacy hardware to drive adoption.

- Build a value layer at the intersection of your software and your hardware.

Then you have yourself a low entry-point, more product reach, and an extraordinarily strong bottoms-up adoption story.

And you can meet your customers where they are, so you can take them where you want them to go.